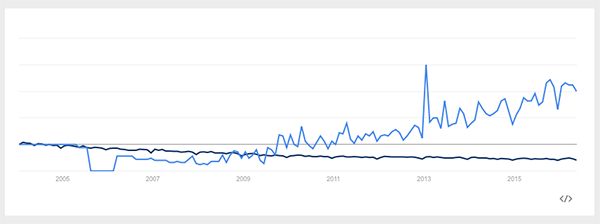

Design thinking is all over the place. Every large organization claims to use it in a way or another to spur innovation, and every place dedicated to hold seminars comes fully loaded with white boards and sticky notes. A quick glance at Google Trends shows how much searches for design thinking consulting help gain in popularity over time, while the whole “consulting” category is more and more losing its appeal to executives. Yet, despite a sustained keen interest, in most cases, design thinking fails to deliver up to its promise. But are we really focusing on the right approach?

Evolution of searches for “design thinking consulting” vs “consulting”

Of Principles and Methods

The core ambition of design thinking was to formalize the process of design, in order to give the capability to apply this principle to all kinds of problems, from product innovation to wicked societal problems. Roger Martin, former dean of the Rotman School of Management, and Tim Brown, CEO of the design company IDEO, have largely contributed to this formalization and helped in popularizing the approach. But this came at a major cost.

For business decision makers, typically non-designers, principles must translate into methodologies to become actionable. Thus, the design thinking principle, defined as “a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success” by Tim Brown, had been repackaged into the now famous “empathize-define-ideate-prototype-test-and-iterate” mantra to get past the corporate doors.

As Ralph Waldo Emerson beautifully nailed it: “If you learn only methods, you’ll be tied to your methods, but if you learn principles you can devise your own methods..” Grabbing the essence of a principle, experimenting in order to understand its implications, and putting it in practice can prove itself to be a difficult task, especially in the case of an emergent principle such as design thinking. This will quickly challenge many of your assumptions about how work gets done and of your mental models. On the other side, sliding from principles to methods will only get you as far as you already know you can go. In many cases, methods act as a prescription, as a how-to approach that will lead you to tweak the context and prune particularities to fit ready-made models.

By restricting design thinking to a method, however brilliant, conceived as a tool for non-designers, its evangelists have seeded the conditions for failure, as the Stanford d.school itself recognized.

An Approach Under Influence

No matter how useful the “empathize-define-ideate-prototype-test-and-iterate” methodology can be in encouraging and training individuals—who tend to act linearly—to think collaboratively and “out of the box,” this methodology oversimplifies the design process. As every experienced designer knows, this process is messy, made of numerous loops and back-and-forth reasoning. While leaving design to designers in pure proselyte mode may have severe drawbacks, such as what I have called the “guru designer” problem, summarizing it into a methodology to bring it within everyone’s reach in a corporate environment exposes it to many biases.

The human mind is such that we tend to step back into our comfort zone whenever possible, even (maybe even more) when we are exhorted to do the contrary. In most organizational contexts, this means putting a heavy focus on linearization, simplification, and rationalization, affecting all activities and tasks. Let us consider how this influences every phase of design thinking as a methodology:

Empathize

In our more and more data-driven business world, it is easy to forget that figures don’t tell THE truth. They just tell A truth, the one you want them to tell. Empathy doesn’t grow from data, it comes from the story that lies behind. Building a story from the data you collect from your customers and users is like presenting a mirror to yourself.

To understand the context in which your customers lie, you must walk in their shoes, and fully grasp the job they are trying to get done. You must also be aware that their context is not yours; failing to keep this in mind will make you miss the broader dimensions of the problem you are trying to solve.

Define

Designers do not tackle new problems with a blank mind, they bring to the table their experience, their own beliefs and history of failures and successes. A great designer looks at the real world and makes connections others don’t see, often allowing him to shape an embryonic solution to trigger further inquiry even before the problem has been properly framed, what Bryan Lawson has described as “the primary generator” in his classical How Designers Think – The Design Process Demystified.

More than often, defining the problem is in fact a matter of abductive reasoning, a back-and-forth navigation between the definition of the problem and the set of conditions put up by the context, much more than a statement like “how could we make our product|service|organization more desirable|useful?”.

Ideate

Common beliefs would want ideation to be the easiest part in design. Recall some background (typically the problem to be solved), distribute some pens and sticky notes, and here you go. The problem is that, unless deliberately set up, this approach doesn’t bring you what you expect. Garbage in, garbage out. Ideas are your most valuable assets, and must be handled as so. They must be confronted with your definition of the problem, they have to be part of the solution, to clarify or to extend some aspect of the problem. Even more, the problem has to be challenged by what comes up during your ideation phase, refined by evidence or even totally rethought. In fact, empathizing, defining and ideating cannot be dissociated as you will need to push all these steps further together until you are able to draft a solution. In the design process, the solution is indissiocable from the problem.

Prototype

Where ideation is falsely considered as easy, building prototypes is often viewed as the most difficult phase by organizations, as soon as it doesn’t concern product innovation. The idea of prototyping a service, and even more a system (such as a team structure), beyond drawing a chart on a piece of paper is a daunting task for people who consider play or corporal expression incompatible with corporate etiquette. It doesn’t look serious enough for them.

Yet, embodying interactions through role playing, or feeling physical space with actual size mockups is the best way to learn about what “the real thing” could be and to avoid many mistakes. Being serious about what you are trying to create doesn’t imply being boring or blankly conventional during the process. After all, following a creative process implies … being creative.

Test and Iterate

In organizational context, almost everything is considered as a project. As a consequence, even in the most agile environment, testing and iterating often translates into “let us build a v0, then we will move to v1, and prepare for v2.” When designing for services or for systems, this approach usually leads to selecting the most important features to build a Minimum Viable Product, then planning for further implementation in subsequent iterations.

Wait… Are you sure that your careful selected features are the ones your customers really care about? While designing, test and iterations mean loading your first version with as many of the features retained during the prototyping phase as you can, in order to learn as much as possible from the real thing. By limiting your initial value proposition, you may ruin all your efforts to understand what your customers and users really need and to provide an adequate answer.

Taking the Daring Path

As a methodology, design thinking isn’t, by far, a panacea to help organizations to transform themselves. Neither is the so-called digital transformation that we keep hearing about day after day. In fact, no methodology will ever be, as they have little more to offer than what organizations are already able to do. Adapting to the uncertain, volatile and complex world in which we now live, requires taking more daring roads, and to relinquish control to be able to experiment with new, maybe disturbing but rewarding, principles without faking.

05/20 update

Design involves bringing into play a complex process. As so, it implies doubt, faith, trial and error, and continuously challenging the assumptions you are building, at macro as well as at micro level. Unfortunately, this leaves very little place for certainties or for “absolute” solutions. By essence, complexity is fractal. More than a methodology, and to be of real help, the “empathize-define-ideate-prototype-test-and-iterate” design thinking metaphor must be understood and used as a kind of “meta-methodology”, as… nothing more than a prototype, requiring to be tested, tweaked or even completely re-invented according to the specific context that is yours.