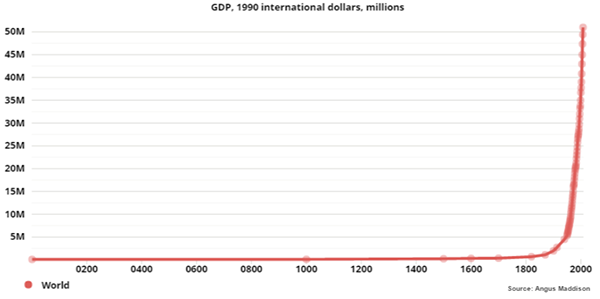

L’entreprise est née sur le principe de la mise en commun des moyens de production, de la promesse de la possibilité d’accéder à des ressources inaccessibles à un individu seul.

Selon Jeremy Rifkin, la réduction des coûts de production provoquée par la révolution numérique ouvre aujourd’hui la voie aux “makers” et rend obsolète l’entreprise traditionnelle, du moins dans la définition que lui donne la théorie des coûts de transaction. Mais cela représente-t-il réellement un progrès social ?

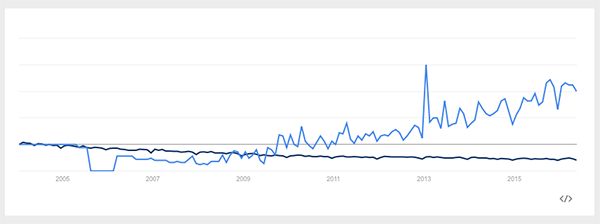

L’irrésistible montée en puissance des plateformes

Au cours des dernières décennies, la notion même de ressource a radicalement évolué. Alors que de multiples moyens de production sont désormais accessibles à tous à faible coût, voire à coût nul, le principal problème auquel l’entreprise doit faire face est devenu celui de l’accès au marché. Dans une société dévorée par l’individualisme et la compétition, chacun se bat désormais pour trouver de nouveaux circuits de distribution pour sa propre production. Il était donc tout naturel que se développent et prospèrent de nouveaux géants, tels qu’Uber ou la Marketplace d’Amazon, dont le modèle repose presque exclusivement sur une plateforme digitale permettant de mettre à disposition de tout à chacun, à nouveau à faible coût, de puissants moyens logistiques globaux.

Si ces plateformes offrent à des individus et à de très petites entités dotés de leurs propres moyens de production (ce n’est pas un hasard si Amazon s’intéresse depuis peu fortement à l’artisanat) une très large exposition au marché, elles partagent une autre caractéristique: une très forte concentration capitalistique. Ainsi, Uber ou AirBnB sont-elles des entreprises privées aux mains d’un nombre très restreint d’actionnaires, et Jeff Bezos, CEO d’Amazon, est-il, de loin le principal actionnaire, direct comme absolu de l’entreprise avec plus de 17% du capital détenu. Dans un monde où la part de l’économie réelle dans l’économie globale se restreint de jour en jour, l’entreprise a troqué la puissance de production contre la puissance financière pure.

Le producteur, cet intermédiaire

Mais ce modèle en plein développement, qui associe concentration du capital avec externalisation des activités de production, est en fait loin de représenter un progrès. L’entreprise préindustrielle s’est construite sur la hiérarchie des rôles et la rationalisation des tâches, cimentant le tout autour d’une “vision” commune que l’on pourrait résumer par “donne-moi une partie du fruit de ton travail, je te donnerai davantage de moyens pour travailler” dans un souci d’efficience globale. L’entreprise industrielle a développé le même type de structure en compromettant la vision, en prise aux enjeux d’une financiarisation progressive, pour devenir la structure malade que l’on connait aujourd’hui, tiraillée entre recherche de sens et recherche de plus en plus exclusive de profit, en grande majorité incapable de réconcilier les deux termes de l’équation. L’entreprise-plateforme, elle, s’est définitivement débarrassée de la propriété des moyens de production en même temps que de la vision interne, la portant au contraire directement vers le client utilisateur de ses services.

Les travaux théoriques de Stephen Vargo et Robert Lusch sur la logique à dominante service et les développements pratiques auxquels ils ont donné lieupour l’entreprise ont démontré qu’un potentiel important de création de valeur existe dans les interactions entre l’entreprise et ses clients. C’est sans doute dans l’exploitation de ce gisement que les entreprises-plateformes se sont montrées les plus brillantes. En externalisant leur production, elles externalisaient également en grande partie l’interaction avec leurs clients. Les systèmes de recommandation et de notation mis en place par la plupart des plateformes (et copié, pour un bien moindre bénéfice, par de nombreux sites de e-commerce) leur ont permis de garder la main sur la qualité de cette interaction. Quelques commentaires négatifs suffisent en effet parfois à radier quelqu’un d’une plateforme.

L’homme dépossédé

Dans ce contexte, en externalisant les moyens de production tout en s’appropriant la relation client et de la création de valeur, les grandes plateformes ont dépossédé l’individu, l’acteur-producteur, de ce qui était jusqu’alors l’essence du travail, à savoir la participation à la production d’une réponse particulière et différenciée à un besoin précis au moyen de compétences spécifiques. La communauté d’intérêts qui donnait son sens à l’entreprise a disparu, remplacée par un marché ouvert où la compétition est attisée. L’individu est devenu à la fois produit et outil, interchangeable et consommable en fonction des attentes des clients et des besoins de l’entreprise-plateforme. La recherche d’efficience qui caractérisait l’entreprise industrielle, et qui, de la mise en place de hiérarchies rigides à l’adoption de stratégies lean, se traduisait par l’optimisation des ressources disponibles, a fait place à une recherche d’efficacité basée sur la quantité des acteurs à disposition de la plateforme.

Si l’entreprise préindustrielle et l’entreprise industrielle pouvaient se prévaloir d’une relation symétrique entre elles et leurs employés (part du fruit de la production contre moyens de production dans le premier cas, production contre salaire dans le second), dont les termes et obligations réciproques étaient formalisés par un contrat, l’entreprise-plateforme ne fournit aucun engagement de réciprocité, l’accès au marché n’ayant aucune valeur de garantie. Cette relation, basée sur des intérêts divergents, est en fait assez proche de celle qui existait au Moyen-Âge entre serfs et seigneurs, lorsque le seigneur louait ses terres en échange d’une partie des récoltes, mais que rien ne garantissait au paysan que cette terre lui donnerait ne serait-ce que le moyen de survivre.

L’entreprise-plateforme représente sans doute le stade ultime de l’économie capitaliste et de la société de consommation. Par contre, que ce soit en termes d’organisation ou d’accomplissement humain, elle ne délivre aucune des promesses qu’une véritable économie des réseaux saurait nous apporter. La quantité infinie de savoir et de connexions que la technologie met aujourd’hui à notre disposition devrait nous permettre de jeter les bases d’une Renaissance éclairée, en lieu et place de quoi nous plongeons dans les aspects les plus noirs d’un nouveau Moyen-Âge, dans lequel on accorde plus de valeur aux données qu’au travail. Nous vivons dans un bien triste monde…

We are living in a sad world. An hyperlinked world. A networked world. In theory, this should mean unlimited, universal and unrestricted access to information. In our societies, this should mean the rise of enlightened democracies, powered by collective intelligence, geared toward people’s well-being and education. In our businesses, this should mean the birth of learning organizations, as described by Peter Senge in his seminal

We are living in a sad world. An hyperlinked world. A networked world. In theory, this should mean unlimited, universal and unrestricted access to information. In our societies, this should mean the rise of enlightened democracies, powered by collective intelligence, geared toward people’s well-being and education. In our businesses, this should mean the birth of learning organizations, as described by Peter Senge in his seminal