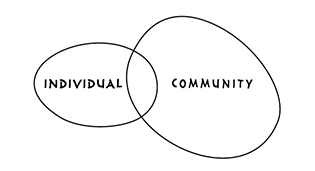

My last post sparked a few amazing comments. Looking back to the little exercise I attempted – representing organizational structure as Venn diagrams – I realize that my view was a bit enterprise-centric. “Customer”, as a concept, is quite reductive when considering the relationships between individuals and organizations. What if, instead of focusing on the world of work inside companies, we considered the larger context in which work takes place? Work, in fact, is the human activity of producing artefacts – goods and services, of course, but also capital, or knowledge – to allow for exchanges to happen. These kinds of transactions – non-market, if we consider exchanges of knowledge as transactions – have existed since the dawn of humanity, amongst the first tribes of hunters-gatherers, encompassing both physical and symbolic transactions between individuals and the community they belonged to. A straightforward world…

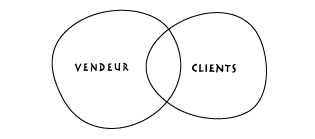

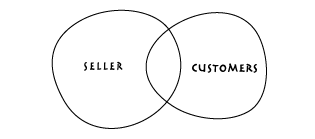

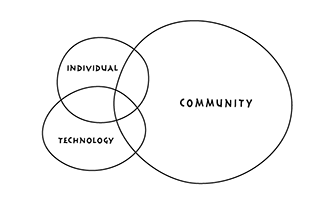

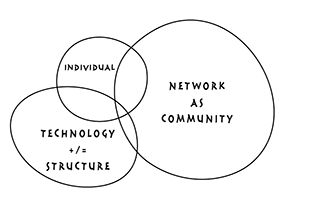

Well, not quite. Starting from the first cut stone, technology has always played a major role in magnifying and extending human capabilities. If we can illustrate the initial transactional context as follows…

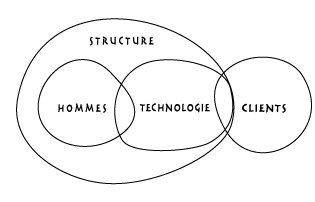

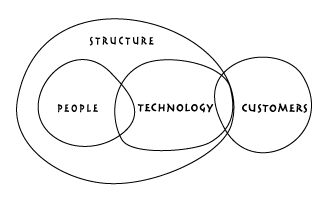

… as we navigate in time from prehistory to history, individual interests more and more lost their importance in favor of the collective. Technology began to allow completion of more sophisticated tasks, often requiring more than one individual for being completed. From one-to-one or one-to-many transactions, production mechanisms, fueled by the growing division of labour, turned into many-to-whatever, giving rise to the need for formal structures to optimize technology driven production.

Productivism and organizational disease

With the Industrial Revolution came an important shift: most of technological breakthroughs didn’t empowered individuals, but required a collective structure to deliver. Not only were firms the logical outcome of economical evolution, but they were a natural fit for the rapid evolution of technology occurring during the XIXth century. It would be childish to say that large corporations are born by technological necessity, but fact is, in this pre-unionist era, that most of the resistance to the world of work taking shape wasn’t caused by deteriorating conditions of working, but directly linked to technology, as François Jarrige describes in Face au au monstre mécanique : Une histoire des résistances à la technique. The Luddite uprisings from 1811 in Great Britain is one of many such examples.

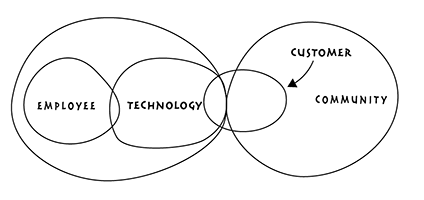

At the same time, another major change took place: the emergence of the nation state. By providing a symbolic as well as practical context in which most community-based exchanges could take place -administration, law, education,… – and securing the identity of communities through a distinct and infrangible territory, it freed corporations from their duties toward the communities they belonged to, allowing them to pursue an economical only mission. The complex dynamics of interpersonal relationships involved in traditional transactions, implying reciprocity and feedback loops, disappeared, replaced by markets only dynamics. In this emerging paradigm, people began to be considered according to a dichotomic prism: they became either employees, for the sake of production, or customers, for the sake of transactions. In the most cynical cases, this duality was meant as an autonomous circle; Henry Ford famously raised his employees’ wage, so they could afford to buy his cars.

Building on the diagram from my previous post, here is how we might represent business in the industrial and post-industrial ages:

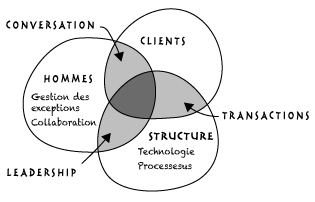

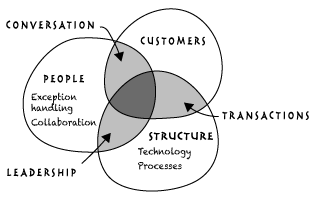

From this diagram alone, it is easy to deduce the symptoms of today’s organizational disease that we witness around us:

- Disengagement from work. Productivism isn’t a human ideal. By reducing employees to production tools, by protecting work from the rest of human activities, organizations have created conceptual and functional strongholds. The premise of recurrent wages isn’t a stirring enough purpose to trigger and sustain involvement in such isolation.

- Hardcore individualism. Customer is king, of course, but propelling consumerism for a century has flattered our ego in unprecedented ways. Businesses have operated in an apparent paradox: to propel mass-production, they have pandered to -an created- individuals’ needs and expectations in a more and more targeted way, encouraging conspicuous consumption and fostering devious hedonistic behaviors. By playing sorcerer’s apprentices, organizations have have allowed this individualistic mindset to blossom inside their walls, facilitated by hierarchical structures and concentration of power.

- Ethical chasm. By disregarding the collective, corporations have grown in isolation from the issues impacting human communities, in some -many?- cases worsening them: environmental degradation, wealth imbalance, cultural inequalities,…

Toward a new world

Yet, a totally new breed of technology has appeared, disrupting industrial age behaviors even faster than precedent technological milestones have helped in shaping them. For the first time in history, a device, the personal computer, when associated to the internet, has become both a tool of production and a tool of consumption, challenging the producer-consumer relationship on which the industrial paradigm was based, erasing the lines carefully drawn between work and other activities, freeing individuals from this dichotomy, allowing them to think differently over their own role and to relentlessly connect with each other.

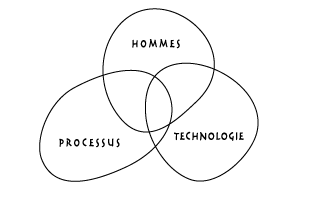

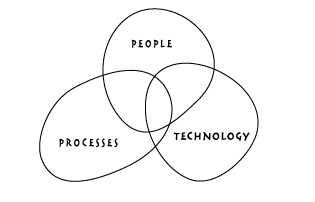

As no surprise, most of the technologies built upon this breakthrough derive from this awareness and share common traits:

- They are personal. Unlike technologies from the industrial age, they are built for the individual, and don’t require heavy infrastructure or strong coordination to be operated. Organizations, in fact, struggle when trying to adapt them to their own command-and-control mindset, stifling their outdated notion of productivity.

- They are adaptive. As Manuel Castells explains, the networks that information technologies enable doesn’t warrants by itself their superiority over centrally structured hierarchical organizations. Their advantage comes from the flexibility, the ability to adapt to changing environments to “de-center performance and share decision making” according to the context they allow.

- They are multi-purpose. These technologies are themselves networked and modular, giving individuals unprecedented ways to make them fit any purpose, and to use them to address goals beyond production or consumption only. Unlike precedent technologies, their impact on the society is not predetermined, and lies on the will of those who use them, for better or for worse.

Hyper-connectivity and dynamic reallocation of resources based on trust are the main characteristics of the new, networked, world unveiling in front of our eyes, allowing the rise of micro-markets and the re-appropriation of production by individuals , who have become both producers and customers.

Our society’s infrastructure, fitted to the precedent centralized paradigm, is slow to adapt. Our compensation-based world of work, backed up by an omnipotent banking system, is curbing our ability to fully embrace a network-based economy. Our nation states which, after having favored the domination of the mechanistic corporation, could paradoxically be a key actor in the rise of a prosumer world, are now too weak to take over this role.

Yet, it is only a matter of time. In our recessing economies, the movement toward individualization and self-determination is hitting the job market, as part-time and contractual work make up a growing part of the workforce. The future of business is about an organization’s capability to create value from, for, and inside networks. The kind of linked structures businesses are more and more forming in the midst of their ecosystem is not flexible enough to avoid the risk of being disrupted by emergent outcomes from the rising collaborative economy. To avoid this disruption, organizations have little if no choice. Internally, they have to behave as networks to adapt to their environment, thus to embrace the organizational principles of wirearchy. Externally, they must act as nodes in the larger networks making up our communities as well as our society: purposeful, supportive and trustworthy. For many businesses, it is a long way to go. But it is the kind of world we, as human beings, have already started living in.