Les expressions ont souvent un sens plus profond que les mots qui les composent. C’est le cas de celles qui décrivent les nouvelles conditions du travail, bouleversées par la montée en puissance des réseaux et de la technologie. La première de ces expressions était l'”enterprise 2.0″, qui désignait la forme la plus représentative de l’activité humaine de production, l’entreprise. Puis vint “social business”, dans laquelle l’organisation était remplacée par l’activité elle-même. Aujourd’hui, la “transformation digitale” est l’expression à la mode, qui ignore complètement le sujet de cette transformation, et qui permet de se référer à des conditions changeantes sans les replacer dans leur contexte. Pure coïncidence ? Il est en fait bien plus facile de traiter du changement sans s’attaquer à des questions bien plus fondamentales autour de la nature et de la raison d’être de l’entreprise. Tout se passe comme si nous étions tellement immergés et conditionnés par nos racines judéo-chrétiennes que nous tenions pour acquise la notion de travail en tant qu’inéluctable péché originel. Pourtant, il devient de plus en plus critique de comprendre la nature et la raison d’être de nos structures pour construire le futur.

L’étape logique suivante

Le changement des structures industrielles en plateformes que nous sommes en train d’observer a des implications lourdes, qui vont bien au-delà de la nécessité de repenser les pratiques managériales. Pour les comprendre, il est utile de se tourner vers la théorie des organisations. D’un pont de vue économique, l’une de nos principales sources de compréhension de la nature des organisations commerciales provient d’un court essai intitulé “La Nature de la Firme“, et écrit en 1937 par Ronald Coase.

Pour Coase, les entrepreneurs engagent des travailleurs sous l’égide d’une entité unique pour min miser les coûts associés aux transactions. Les entreprises, et leurs mécanismes internes, seraient ainsi bien plus rentables que les effets d’offre et de demande générés dans les marchés. Pourtant, comme je l’ai déjà écrit, cette efficacité a disparu, alors que la technologie permet à présent à tout et à chacun de produire biens et services à un coût quasiment nul. La transformation de l’entreprise en plateforme, mettant à profit les compétences d’individus en réseau pour fournir ou même produire des biens et des services à la demande, et en cela donnant naissance à ce que nous appelons l’économie du partage, est l’étape logique suivante. Mais doit-on l’appeler un progrès ?

La revanche des marchés

La consommation de masse et les effets directs des mécanismes de marché ont fait baisser le prix de la plupart des biens et services que nous utilisons dans la vie courante. Mais ce qui est vrai pour l’individu ne l’est pas forcément pour l’entreprise. Celle-ci, par exemple, payera au minimum dix fois plus cher que moi la même connexion internet par câble. Réserver un vol par l’intermédiaire d’un programme corporate coûte en général bien plus, même compte tenu des marges arrières, que celui que je pourrait réserver par moi-même. Dans ce genre de cas, les coûts de transaction associés sont bien plus élevés pour une entreprise que pour une personne physique, à cause de toutes les couches supplémentaires qu’ils incluent: les taxes et les coûts nécessaires au maintien d’une structure bureaucratique, bien sûr, mais aussi et surtout, les coûts permettant d’assurer la répétabilité et la fiabilité de la transaction.

Pour l’acheteur, la plupart des transactions impliquant une plateforme ne prennent pas ces coûts en compte, et n’assurent qu’une fiabilité minimale par rapport aux marchés. Si ces plateformes voulaient assurer une meilleure répétabilité, elles devraient alors recourir à davantage de bureaucratie et mettre en place des procédures plus strictes. D’un point de vue purement transactionnel, les plateformes ne présentent qu’un avantage artificiel par rapport aux entreprises industrielles, avantage qui risque de disparaître une fois que les marchés nouvellement créés se stabilisent et deviennent plus efficients.

Technologie versus travail

Il y a une autre manière de considérer la nature des organisations sur le plan économique. La théorie de la firme basée sur les compétences, au lieu de considérer le mécanisme générique qui donne naissance à l’entreprise et lui permet de grandir, se concentre sur la manière dont elle s’organise et fonctionne afin de prendre l’avantage sur les marchés et sur ses compétiteurs.

A partir de cette vision, et en vue de mieux expliquer la manière dont les entreprises évoluent et s’adaptent à des environnements en changement rapide, la théorie basée sur le savoir considère le savoir comme étant la compétence la plus importante de l’entreprise. Pour une entreprise-plateforme reposant sur un réseau de travailleurs, reposer sur l’intelligence collective apparaît comme une promesse fabuleuse. Le fait est que l’essentiel du savoir sur lequel elle s’appuie provient d’algorithmes de plus en plus sophistiqués, et non de compétences humaines. Le Turc Mécanique d’Amazon tire sa puissance d’une savante division du travail informatisée, la force de BlaBlaCar provient davantage de la précision avec laquelle l’entreprise relie les courtes distances que sont prêts à partager les automobilistes en trajets à longue distance. Cette liste pourrait continuer à l’infini. Du point de vue de la théorie basée sur le savoir, les entreprises-plateformes représentent le futur pour la technologie, pas pour les travailleurs.

Des business modèles jetables

La théorie des compétences dynamiques, exprimée et développée par David Teece au début des années 90, offre une vision plus large sur les compétences de la firme. Dans The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms: an Introduction, coécrit avec Gary Pisano, il jette les bases de cette théorie, écrivant que :

“Nous postulons que l’avantage compétitif des entreprises provient des compétences dynamiques ancrées dans des routines de haute performance opérant à l’intérieur de l’entreprise, enchâssées dans les processus de l’entreprise, et conditionnées par son histoire. A cause des imperfections des marchés, ou plus précisément de la nature non négociable d’actifs “softs” tels que valeurs, culture et expérience organisationelle, ces compétences ne peuvent en général pas être acquises; elles doivent être bâties”.

Pour Teece, la réorganisation des ressources disponibles, à travers la reconfiguration de ses actifs, à travers l’apprentissage et la construction de routines à haute performance, sont les éléments constitutifs d’une entreprise.

Dans le cas d’une entreprise-plateforme, la plupart des ressources sont externalisées. Le travail est outsourcé, ainsi que la plupart des compétences susceptibles de lui permettre d’évoluer. Sans cadre organisationnel favorable, la construction de routine et l’apprentissage sont laissé à l’initiative de l’individu, et ne peuvent pas être capitalisés à l’échelle de l’entreprise, à moins que les personnes travaillant pour elle ne forment un réseau aux connexions fortes. L’innovation ne peut exister qu’au niveau du centre, limitant encore davantage la capacité des plateformes à s’adapter à un nouvel environnement. Fait est que la plupart de ces entreprises ne développent leur avantage compétitif que d’un nombre très limité d’idées et de processus, au sein d’un business modèle fixe. Lorsque celui-ci est remis en question et l’entreprise est incapable de le poursuivre, elle passe en général à quelque chose d’autre. L'”économie réelle” (la production de biens et services, excluant l’enrichissement uniquement financier) dans son ensemble est en train de devenir un terrain de jeu pour le modèle startup. Pivoter plutôt qu’évoluer, quelles qu’en soient les conséquences pour les travailleurs.

Une histoire d’épuisement

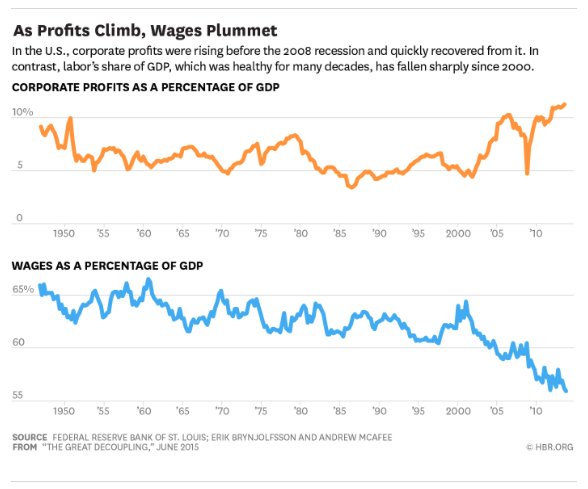

La seule direction dans laquelle l’entreprise-plateforme peut être vue comme un progrès est en fait négative. L’histoire de l’entreprise, sous l’angle de ses relations avec la technologie, que l’on peut faire remonter à l’invention de la navette volante par John Kay en 1733, suit sa propre logique radicale: l’épuisement des ressources. La poursuite de la productivité, typique de la Révolution Industrielle, a poussé les enterprises vers la surexploitation des ressources naturelles et de l’énergie fossile. L’étape suivante a consisté -et consiste toujours pour beaucoup d’entreprises- en efficacité et en réduction des coûts, menant progressivement à l’épuisement des ressources internes et à l’agonie programmée du régime salarié. Le graphique ci-dessous montre bien la décorrélation entre profits et masse salariale globale.

En encourageant la marchandisation de services normalement gratuits dans un contexte réellement social, les entreprises-plateformes ne sont-elles pas en train de mener l’épuisement vers une nouvelle étape, entamant le tissu même de notre société ?

Un nœud de contrats

Ne nous laissons pas tromper par le fait que l’entreprise-plateforme utilise les réseaux en tant que principale ressource. La théorie des organisations semble nous dire qu’elles représentent une impasse, un maximum local, dans l’évolution du monde du travail, et sont, sous bien des aspects, une régression par rapport à l’entreprise de l’ère industrielle. Si nous voulons envisager un futur plus radieux, nous devons définitivement nous mettre à la recherche de structures plus soutenables. Là aussi, la théorie peut nous fournir certains indices.

Revenons à Coase, ou plutôt à Oliver Williamson, qui, à partir du travail de Coase, a développé la théorie des coûts de transaction. Pour Williamson, plus une transaction requiert un savoir spécifique, et plus le résultat comporte d’incertitude, plus il y de chance pour qu’elle se produise au sein de l’entreprise pour en minimiser les coûts induits. Au cœur de ce concept se trouve l’idée que cette optimisation est liée à deux niveaux de relation entre les acteurs impliqués. Tout d’abord, un réseau de liens contractuels, en interne aussi bien qu’en externe entre acheteur et vendeur. Ensuite, puisque ces contrats sont considérés comme incomplets -ils ne peuvent pas couvrir toutes les situations possibles-, une couche de gouvernance basée sur l’autorité, permettant à ses porteurs de prendre des décisions dans tous les cas non prévus par les contrats.

Dans son désir de contrôle, l’entreprise industrielle a développé des comportements bureaucratiques, renforcé les hiérarchies en tant que structures d’autorité, et contribué à forger la loi des contrats à sa propre convenance, transformant peu à peu le principe de bonne foi en camisole formelle, ainsi que l’a exposé Grant Gilmore dans son classique The Death of the Contract. L’entreprise-plateforme suit un chemin différent, éliminant la couche de gouvernance pour s’en remettre aux marchés pour résoudre ce qui n’est pas couvert par les contrats.

Une plongée dans l’inconnu

Ce recours aux marchés est-il vraiment une solution soutenable ? Je ne le crois vraiment pas. La raison d’être, ainsi que la mécanique, des transactions humaines ne se réduit pas à la dynamique des marchés. Le besoin de se réunir pour réduire les coûts impliqués dans ces échanges est une constante, et pas uniquement dans un point de vue économique. Notre challenge, pour être capables de guider les entreprises aujourd’hui, est de commencer par comprendre la forme que vont prendre les choses, tout autant les structures organisationnelles que le cadre contractuel qui reliera ces structures en interne. A une époque où notre vie privée et notre vie professionnelle se mélangent, et que le lieu du travail s’étend de plus en plus dans l’espace de la ville, nous devons également comprendre qui sont les acteurs de cette nouvelle dynamique, et quelle est la responsabilité des uns envers les autres.

Bien sûr, une profonde transformation digitale est à l’œuvre, et nous avons besoin de nouveaux principes et de nouveaux cadres organisationnels. Nous avons également besoin de reconnaître humblement que nous plongeons dans l’inconnu.

Image: Howard Pyle illustration d’un pirate sur la planche, tiré du livre d’Howard Pyle “Book of Pirates”. -domaine public-